As Mark Zuckerberg testified in front of the U.S. Senate Commerce and Judiciary committees, Representative Ro Khanna watched in dismay. This was less because of what the Facebook co-founder and chairman did say—for the most part, bromides about privacy, security and censorship—than because of what the lawmakers arrayed before him didn't.

"This was a missed opportunity," Khanna lamented later that evening in a text message. "The hearing revealed a knowledge gap in Congress about technology." Many of the men and women questioning Zuckerberg were about twice his age, and some were quite a bit older than that. They knew that adversaries like Russia had weaponized social media networks like Facebook and Twitter, but the particulars of the problem clearly eluded them. The 44 legislators who took turns quizzing Zuckerberg showed only a cursory understanding of data collection and encryption, and the lengthy hearing quickly devolved into the kind of exasperating technology tutorial one dreads having to give aging relatives.

It was an amusing day for the purveyors of humorous internet memes. But anyone anxious about the obviously uneasy marriage between democracy and digital technology would not have been reassured. Zuckerberg left Capitol Hill without having to explain in any appreciable detail the failure that brought him there in the first place: the improper use of data belonging to 87 million Facebook users by data research firm Cambridge Analytica, which was conducting microtargeting work for Donald Trump's presidential campaign. He did offer apologies and reassurances, but these were vague enough to not be especially reassuring.

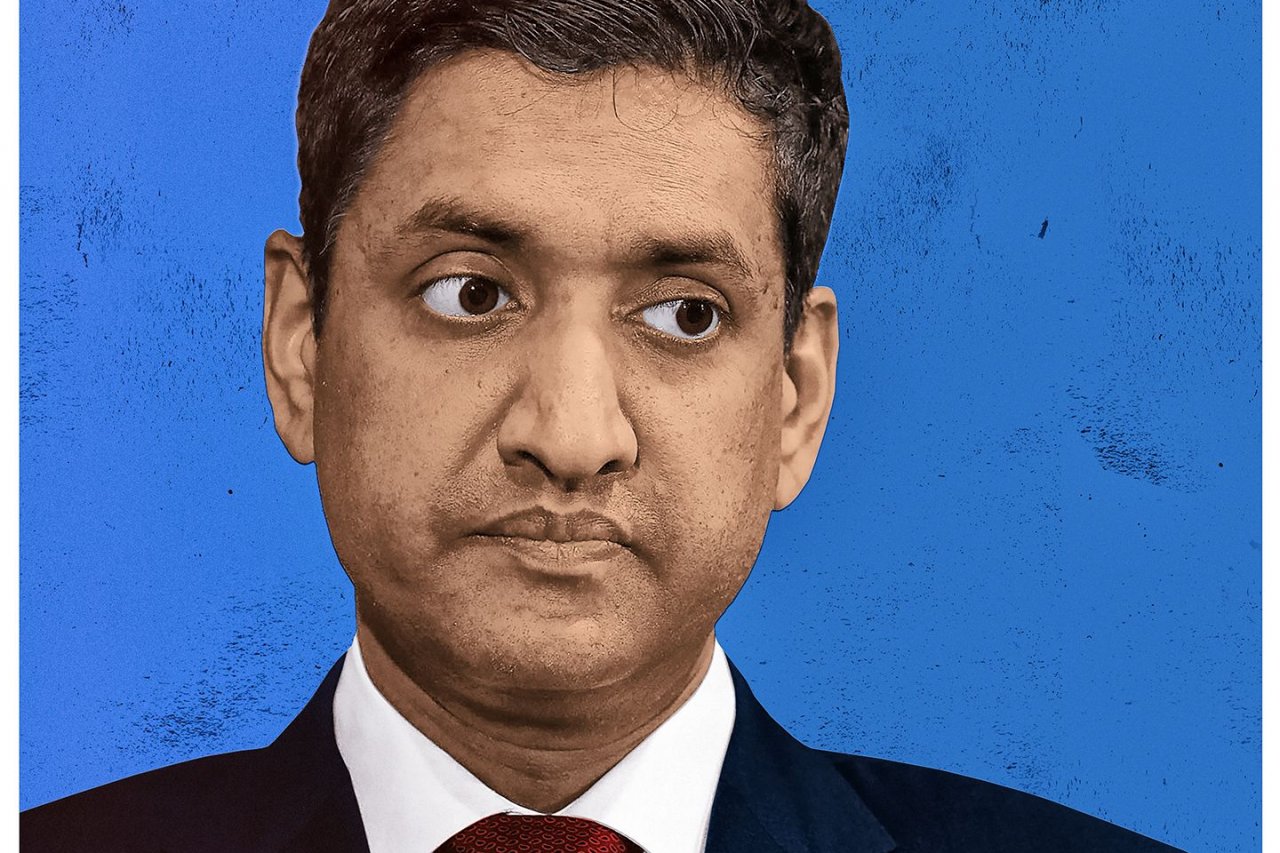

Only eight years older than Zuckerberg, Khanna has been called "Silicon Valley's ambassador to Middle America." California's 17th congressional district, which he has represented since 2017, is home to some of the most successful corporations in the world: Apple (market value: $892 billion, as of April 16), Intel ($245 billion), Yahoo (now part of Verizon, whose market capitalization stands at $197 billion) and Tesla ($50 billion). Alphabet ($726 billion), with its Googleplex, is one district over, as is Facebook ($480 billion), with its thumbs-up icon announcing its Menlo Park Headquarters, at 1 Hacker Way.

That address captures the mood of Silicon Valley a decade ago: whimsical, cheeky, maybe even hubristic. This was before anyone had ever heard of the Internet Research Agency, where Vladimir Putin's minions were waging a new kind of war. Psychographic data, of the kind Cambridge Analytica supposedly collected, was not yet for sale to politicians looking for an edge. Trolls were the stuff of medieval legend. And coding savants could not have expected to be lectured by the likes of Senators Chuck Grassley and Dean Heller, as Zuckerberg was earlier this month. The thumb is still there, at 1 Hacker Way, but the joke is no longer funny.

"I believe representing Silicon Valley is one of the most important jobs in American politics," Khanna says. To represent Silicon Valley is to speak and account for a techno elite given far more to self-celebration than introspection. Aware of the region's surpassingly good fortunes, and of its closely related tendency to hubris, Khanna has tried to export the former while arguing that it is necessary to tame the latter. He believes that the success of the tech sector is replicable and could serve as economic balm for other parts of the nation, particularly those where mining or manufacturing can no longer vault blue-collar workers into the middle class. Despite troubling disclosures about Facebook and its peers, he believes that most any community would welcome Zuckerberg, along with his Cambridge Analytica problem.

The same week that Zuckerberg testified on Capitol Hill, House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi selected Khanna to draft an Internet Bill of Rights. It was a significant show of confidence in the House freshman by Pelosi, a veteran of the chamber renowned for her political acumen. Although it is impossible to say what an Internet Bill of Rights will look like, Khanna has long proposed such a measure to give Internet users clarity over the data they share as they click through Facebook photos or shop on Amazon.

The Internet Bill of Rights would, in turn, prove a major test of just how much regulation Silicon Valley is willing to countenance. Big Tech has been a remarkably cagey industry, in part because it knows it gives us what nobody else can. It knows that even as we complain about hegemony, we order diapers on Amazon, instead of walking to the corner store. World leaders spar on Twitter, while chefs who once wanted to impress critics now think about what will look good on Instagram. At the same time, Reddit trolls disseminate fake news, which Google algorithms uncritically promote, while terrorists talk freely on WhatsApp, protected by the messaging service's encryption. Silicon Valley is becoming a victim of its own explosive growth, like the too-big-to-fail Wall Street banks that failed in 2008, plunging the nation into a recession.

Khanna is aware of souring public opinion and has tried to both acknowledge it and reshape it. "You can't be an island of success," he says of the district he represents. "We have to answer the nation's call." If Silicon Valley can answer that call with "humility," Khanna says, the tech behemoths can avoid the kind of onerous regulation other liberal legislators are calling for, such as the General Data Protection Regulation that will go into effect in Europe in 2018.

Khanna's indefatigable optimism has positioned him as a potential leader in a Democratic Party unable to reconcile its progressive and centrist elements and desperate for new faces. As a member of the Progressive Caucus, Khanna has advocated for liberal policies such as expansion of the earned-income tax credit. But his corporate past—and corporate constituency—keep him from veering too far into the sort of political fantasy for which Northern California is sometimes known. He may be just what the party needs, a moderate by temperament but by no means a centrist.

"You can have a bold progressive vision coming from Silicon Valley, rooted in patriotism," Khanna says. "And I guess the case study is they elected me."

Yet amid continuing calls to #DeleteFacebook—as well as for Twitter to suspend problematic accounts and Google to live up to its famous "Don't be evil" motto—that sunny vision is increasingly hard to sell, in Washington and elsewhere. And that has forced Silicon Valley's ambassador to play crisis manager, urging patience and promising reform from an industry that has never felt the need to listen to politicians.

'A Legend in Our Family'

If there is an obverse to Trump's America, it is CA-17, a hilly, 185-square-mile refuge south of San Francisco. To the northwest is San Francisco, aglitter with the towering new symbols of techno wealth. On the opposite side of the shimmering bay rise the hills of Oakland and Berkeley, where the graying warriors of the 1960s shuffle down the aisles of organic groceries. The district has only ever sent two Republicans to Congress, the last of them nearly 30 years ago. In 2016, Hillary Clinton won the greater Silicon Valley area with more than 70 percent of the vote; Trump was even less popular here than he was in Manhattan.

Khanna represents both the hippies and the techies, but it's not hard to divine where the sympathies of the former Stanford economics instructor lie.

His parents immigrated to the United States from India in 1968. Because of his name and his dark brown skin, Khanna is one of those Americans fated to field questions about where he is really from. The answer is Philadelphia, where he was born in 1976. But it is also India, where his maternal grandfather, Amarnath Vidyalankar, was an activist and politician who spent time in prison. "He was a legend in our family," Khanna says, calling him "the deep inspiration for entering public service."

Shortly after Khanna was born, his family moved to the prosperous Bucks County suburbs north of Philadelphia. The neighbors, uniformly white, were suspicious. There had been an Indian family on the block before who had not decorated their house with Christmas lights—a statement of cultural defiance, in the local view. The Khannas adorned their house for the holidays, defusing fears. He happily spent his childhood in the town and his parents live there still.

Khanna's patriotism is rooted in this suburban experience. "We're constantly embracing history and culture by reshaping. But we can't reject such a thing as American culture," Khanna says. "We should have respect for certain traditions. I don't think we can be a rootless communal culture."

The mere notion of national culture is anathema to many liberals, who now consider it almost a byword for xenophobia. Khanna acknowledges as much, while also realizing that Democrats have largely ceded patriotism to Republicans. "We need to define American culture in a way that's inspiring," he says, one that embraces and includes.

It's a kind of patriotism tailored to CA-17, the only majority-Asian district in the United States, a miniature of the happily multicultural America that Obama promised was about to come into being. A full 71 percent of workers in the valley's technology sector are immigrants.

This inspirational message would, of course, need a messenger. "You need someone who, intrinsically, in their gut, conveys that the 21st century will be a shining moment for American exceptionalism," Khanna says, without quite saying that he would very much like to be that person.

'A Huge Opportunity'

In the spring of 2004, The Nation wrote about a spate of liberal challengers to sitting Democratic members of Congress who supported the war in Iraq. "The most serious" of these candidates, The Nation declared, was Khanna, then 27 years old.

At the time, Khanna was new to politics, at least as far as his own electoral prospects were concerned. Years before, as a student at the University of Chicago, he'd knocked on doors for a young politician from nearby Hyde Park: Barack Obama. After law school at Yale, followed by a brief stay in Washington, Khanna moved to the Bay Area, where he worked as a lawyer in private practice, as Silicon Valley was recovering from the dot-com burst of 1999-2000. He lost the 2004 primary but, five years later went to Washington anyway, appointed as a deputy assistant secretary in the Commerce Department by President Obama.

Khanna remembers being confounded by the fact that the department was headquartered in a building named for Herbert Hoover. Khanna knew of him only as one of the nation's worst presidents; he soon learned, however, that Hoover was an "extraordinary commerce secretary," as he puts it today, one who helped spur the rise of the commercial aviation industry and reformed the Bureau of Standards, which helped streamline and clarify business practices.

In 1922, Hoover wrote a book, American Individualism, in which he espoused what he called "progressive individualism," with capitalism curbed by a muscular federal apparatus. There was a utopian quality to the book, and Hoover would have been a perfect ambassador for Silicon Valley with his vision of a beneficent capitalism. And in a way, that is his role today. Hoover Tower looms over the campus of Stanford University, where tech giants like Yahoo and Google were born, and the Hoover Institution, a prominent conservative think tank, is housed on campus.

Khanna's approach to Silicon Valley has some touches of Hooverism. He does not believe that onerous regulations are necessary, but he understands that if companies like Facebook, Google and Twitter resist transparency on a variety of issues—data privacy, Russian-controlled accounts that influence our electoral process, a near-monopoly on advertising enjoyed by the first two of those companies—transparency will be forced upon them.

"This is a huge opportunity for tech leaders to work with Congress," Khanna says. Otherwise, he warns, the regulatory power will fall to "a bunch of bureaucrats who, frankly, don't know much about tech," intellectual siblings of the senators who haplessly interrogated Zuckerberg. If regulation is inevitable, better that regulation be informed by the industry in question.

The Rust Belt Safari

"You can blend technology optimism with a progressive vision," Khanna likes to say. But he's a somewhat awkward fit with his party's left wing. It doesn't help that he's worth at least $27 million, making him the fourth-richest member of the exceptionally wealthy delegation from California (total worth: more than $439 million, with Darrell Issa of the San Diego area topping the list). Khanna's wife, Ritu, is the daughter of Ohio automobile parts magnate Monte Ahuja.

A Republican might well celebrate these as particularly American success stories, but

"we were a little nervous," offers Mark Pocan, the Democratic congressman from Wisconsin who co-chairs the 77-member Progressive Caucus. He says, however, that his fears have since been allayed, as Khanna has come out as an anti-trust crusader and an advocate for expanded Medicare. "I could see him being the person on any committee or any issue," Pocan says.

So can others, who have noted Khanna's persistent ambition, his obvious desire to spend no time as a House backbencher (he is one of very few first-termers to have moved his family to Washington). Khanna disconcerted many Democrats by endorsing California State Senate leader Kevin de León, who is seeking to unseat U.S. Senator Dianne Feinstein, whom some regard as insufficiently liberal. A columnist for The Mercury News questioned Khanna's "credentials as a kingmaker," given that Feinstein had been in politics for longer than he'd been alive.

At the same time, Khanna has declined to take a far easier means of self-promotion. Unlike many of his House colleagues, he is not especially interested in impeachment. His Twitter feed is not rife with theories about collusion, what Trump was doing in Russia in 2013, how Jared Kushner wooed real estate investors from the Mideast. Instead, as he put it, there is a more basic question: "Where do we want to take America?" For all his faults, Trump had an answer. Democrats have yet to find one. Khanna is among several young Democrats in the House who see economic progressivism as a better path than endless parsing of the Mueller investigation.

It helps, of course, that his district generates more wealth than many small nations. For all the Silicon "districts" out there, nobody has yet replicated the valley's success. But Silicon Valley is a paradise only for those who can afford it. Glimpse the homeless clustered under freeway overpasses, and the market success of Big Tech can seem like a market failure. Khanna has tried to celebrate the valley while condemning the inequalities it has fostered. "I don't want to live in the Silicon Valley that only has Facebook or Google engineers able to live here," he said at a recent forum on affordable housing.

To survive, he believes, the culture of Silicon Valley must be exported beyond the Bay Area. When that happens, he imagines the entitlement will dissipate, like the fog over San Francisco in late afternoon. "We can't have all of the jobs, all the capital, all of the resources just in Silicon Valley," he says. "It's not good for these companies. It's not good for America." He has worked with Representative Hal Rogers, Republican of Kentucky, on Silicon Holler, a project to bring tech jobs to Appalachia. And he recently toured venture capital firms in the Midwest with Ohio Democrat Tim Ryan in a trip dubbed the "Rust Belt Safari."

And he regularly returns to the Bay Area, holding a monthly town hall in his district. At the one in February, Khanna tried to allay constituents' concerns about North Korea, the loss of civility, Russian meddling. Khanna mentioned his trip to Kentucky, joking that his Indian background had been far less alarming to the people there than the fact that he represented California.

"We are a community that believes in America's future," he said. "If we can make this district a model for the kind of America that we want to see—I think that is the best antidote to the policies of Donald Trump."