How a fruit-shaped brain tumor halted Jeannie Gaffigan’s fast and funny life—and taught her how to really live.

By Stephen Filmanowicz

To know Jeannie Gaffigan, it seems, is to describe her as a superhero.

She’s “an unstoppable woman,” you’ll read in books and magazines — “a force to be reckoned with,” “a multitasking whirling dervish.”

She started creating reactions like this as far back as her days as a Marquette theatre major. Gaffigan, Comm ’92, Hon Deg ’18, was Jeannie Noth back then, gobbling up any and all challenges, from stage-managing student productions to building stage sets and getting cast in acting roles in hip café productions by a hotshot local director. If the wardrobe room started resembling something out of a hoarding show and needed reorganizing, she’d knock that out too.

Fast-forward five years or more and cue these words: “Oh my God.”

That’s Jim Gaffigan, Hon Deg ’18 — Jeannie’s partner in marriage, parenting and comedy — reacting countless times under his breath “in sincere bewilderment” at Jeannie and what she can accomplish.

The first time came a day after their first lunch together. Just a few years into a New York theatre career, Jeannie had already established a nonprofit after-school program, Shakespeare on the Playground. As the couple took shaky steps toward a romance, Jim accepted an invitation to visit a church gymnasium where middle schoolers were practicing to perform Romeo and Juliet set to hip-hop music.

What he saw stunned him — “a sea of kids,” many from nearby public housing blocks, and just a couple of theatre-world volunteers helping Jeannie. “I watched as this human cyclone choreographed and inspired the whole operation,” he writes. “Most impressively, the kids were engaged, interested and having fun. Jeannie somehow thrived and excelled in the chaos.”

“OK, this woman is crazy,” he thought. “But there’s nothing she cannot do.”

By 2017, more than a dozen years and five children into her marriage with Jim, Jeannie had taken high functioning to new heights. Professionally, she had co-written and directed a string of Grammy-nominated comedy specials and served as lead writer and executive producer of a popular cable sitcom based on her life with Jim. She was the undisputed CEO of their household, meeting the nonstop needs of the five kids — six if she counted her husband.

That spring, though, the unthinkable happened. Something stopped Jeannie. It was a pear-shaped tumor wrapped precariously around her brain stem, discovered when she lost her hearing in one ear. Its successful removal by a renowned surgeon led to a wave of unexpected complications that left Jeannie clinging to life in an ICU with severe pneumonia, cut off from her children for weeks and deprived of even a bite of food or drop of water for months.

As Jeannie writes in her heartbreaking, heartwarming memoir, When Life Gives You Pears, those days were harrowing and humbling. The words “trauma” and “excruciating” come up a lot when she talks of them, and she owns up to being far from a pleasant patient. But that’s just part of the story. The pages of Pears are somehow ripe with laughs and gratitude, no bitter fruit. They reveal that Jeannie had been doing a lot more than busy overachieving all those years. She’d been amassing exactly what she’d need — the faith-, family- and humor-filled world — to make it through hell. And, probably, learn a few things that’ll help in getting to heaven, too.

When Jeannie Noth moved to Manhattan after Marquette, she settled onto the kind of lovably ragged downtown block, still undiscovered by rehabbers and real estate agents, that worked for an aspiring actress taking her share of catering jobs to make ends meet.

There was a deli across the street, a subway stop and dry cleaners around the corner, and a big Catholic church one block down. Catholicism had been a given in her house as a child. Her mother — who’d met her father when they were both theatre students at Marquette — had even kept a large statue of the Virgin Mary in the family living room. With dad — The Milwaukee Journal’s longtime theatre critic — she’d pack up the nine Noth children on Sunday mornings for the family Mass at Church of the Gesu.

When Jeannie got to Marquette herself, theology courses and Masses with her family fed her faith, but not in an overly serious way. God was a buddy figure back then. “If I was in a rush to get somewhere, I’d say, ‘Hail Mary, full of grace, help me find a parking space,” she relates with a wink.

But in this enormous new city after college, Jeannie found the nearby church comforting. “It was like God was saying, ‘Hello,’” she recalls. “I mean, I was going to see this church all the time. So, when I went in there, it was like home. I felt like, OK, this is part of my life now.”

Jim Gaffigan was another fixture of her street — the big, pale blond guy who lived across the street from the church. After a long run-up full of half acknowledgments on the sidewalk, they bumped into each other in the narrow aisles of a Korean-run market and joked about whether they knew each other. Jim ended the conversation with a wisecrack: “Hah, we’ll probably get married.”

As they explored an interest in each other, they discovered some uncanny overlap. Both were from cities on Lake Michigan, his in northern Indiana. She was the eldest of nine, he the youngest of six. And he, too, had graduated from a Jesuit university, Georgetown.

“There were things about us culturally that were very familiar. We just clicked,” Jeannie says with a hard emphasis on that last word. Other boyfriends had been bewildered by her manic devotion to the arts, including the youth theatre program she’d just founded. “There was nothing like that with Jim,” she says. “He was just as passionate.”

Work actually helped forge their bond. Soon after the pair met, Jim waltzed into a dream scenario — a lead role in a network sitcom based on some Midwesterner-in-New York material he’d performed on the Late Show with David Letterman. As production neared, he wondered what on earth a comedian with little acting experience was doing in his position. “Well, this happens to be my forte,” Jeannie jumped in. “I’ll coach you on your scenes.” Team Jeannie and Jim was born.

The show ran only one season on CBS, but Jeannie and Jim were just getting started. To produce a CD for Jim to sell at shows, Jeannie sat with her microphone in enough comedy clubs to start offering feedback — which lead-in for a joke worked better, or which progression of bits achieved better flow. “Working together — that’s when things got serious,” says Jeannie.

Jim even turned something funny she said into a joke he used on a late-night TV show. The next day, he told her he’d “killed” with it. “He sounded surprised, but I was so happy,” she remembers. “I thought, ‘Wow, this is something that can bring me such joy, working with this guy.’”

Jeannie got Jim’s comedic voice: at times dark and sarcastic but with a playful, probing sense of the absurd and, of course, a deep affection for eating. And as their creative partnership took shape, she helped enlarge his perspective. When marriage and kids followed, their comedic world grew to absorb them.

And their faith too. The Jim she first met was a cultural Catholic: As he confessed to her, he “rooted for Notre Dame.” But during their courtship, she began dragging him along to Mass, assuring him he wouldn’t flare up upon entry like “foil-wrapped bacon in a microwave.” With time, he needed less pulling. The couple got married in that church and made it part of their life together.

As their brood grew, the big Catholic Gaffigan family stood out as a supersized anomaly in the New York comedy world. A religion writer for The Washington Post even wrote a piece that left Jim feeling “outed as the Catholic comic,” says Jeannie. But there was no turning back. Something in him rebels against the usual expectations imposed on comedians, Jim said last year on the podcast Armchair Expert with Dax Shepard. “I almost wonder if it’s my way of saying, ‘You know what the most rebellious thing I can do is?’ To say, ‘I believe in God.’”

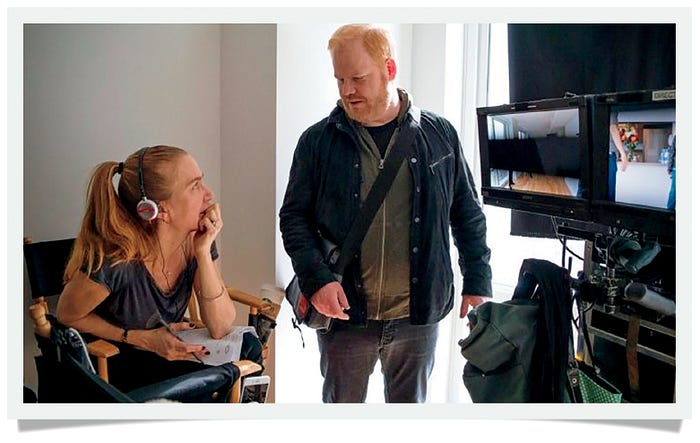

When Jeannie and Jim took their writing partnership to new heights in 2015 with the creation of another TV series, The Jim Gaffigan Show on cable’s TV Land, it put a lightly fictionalized version of their family life center stage. There were Jim and Jeannie (played by actress Ashley Williams), five kids and a few regulars — Jeannie’s gay best friend, Daniel, and Jim’s comedy buddy, Dave, a Jewish atheist lothario. And, yes, there was a nearby Catholic church with an African priest, Father Nicholas, popping into his share of scenes and often trying to wrangle Jim in for a confession as he shuffled past the churchyard.

America, the Jesuit weekly magazine, saw a “great feat” in the show’s integration of faith as an everyday part of sitcom life. Writer Bill McGarvey hailed the Gaffigans’ on-screen world as “simply an amplified comedic version of the messy and complicated lives that most American Catholics — and people of all faiths — unconsciously negotiate every day.”

Jeannie served as lead writer and showrunner, responsible for everything from concept and casting to set design, roles she’d been preparing for since her throw-anything-at-me days in Marquette Theatre. For a creative whiz and admitted control addict, pulling the levers that made the show tick was heady stuff — “the most creatively fulfilling thing I’ve done in my career,” she calls it, “a hundred percent.”

There was just one problem. Working as executive producer and showrunner immersed her in the idea of family life — even a simulacrum of her own family — but left her “living and breathing” television production. “At a certain point, you’re just not home,” she explains. “I came to wonder, ‘Am I just making this up? I’m going to stop being the Jeannie of the show pretty soon.’”

Though the show was popular enough to keep rolling, Jeannie and Jim pulled the plug on it after two seasons in order to be there to see their kids grow up. It was a rare case of Jeannie deliberately slowing down her life, at least a little. (She’d soon find time to direct another Grammy-nominated comedy special, Cinco.) The next time she’d slow down it would be a hard stop — and not by choice.

In a poignant passage in When Life Gives You Pears, Jeannie comes to after 11 hours of surgery and realizes what just happened. Then, she realizes that she just realized something — her faculties are intact. “I’m me,” she sings to herself, flooded with relief.

It’s a sweet moment but, before long, a cruel one. Although her thinking brain would be fine, her tumor had been entwined with the cranial nerves connecting her brain and bodily functions. Hours into her recovery, it would become clear that either the tumor or its delicate extraction had injured the nerves controlling her vocal cords and her throat’s ability to keep air and saliva in their assigned places. After peacefully nodding off, Jeannie awakes in the startling setting of the ICU with a worsening case of pneumonia, caught when she breathed in saliva while asleep.

In the days that follow, her functioning consciousness becomes an enemy of sorts, heightening her awareness of the tubes down her throat and nose, the strict orders forbidding food or water by mouth, the energy drained from her body when she desperately needs to get home to her kids and their by-then multiplying needs. “I was confronted with the dark part of myself,” she writes. “The part that wants to control everything. The furious part.”

Ahead of her lies an agonizing recovery, a soul-shaking spiritual trial. Making it forward requires summoning every internal and external healing resource she can muster. As the subtitle of her book suggests, faith, family and funny people — and the grace they eventually lead her to — become Jeannie’s real superpowers.

By this point in her life, her faith is mature. Revealing in Pears’ description of the frantic run-up to surgery are the religious folk Jeannie has on spiritual speed dial — Sister Mary, Deacon Paul, Father Jonathan. More than one had shepherded Jeannie (and Jim) through faith-deepening crises, including miscarriages and a newborn death that had brought Jeannie emotional pain like she’d never felt before.

God is no longer Jeannie’s buddy, but rather “a mystic, all-knowing presence” and “a loving, merciful caregiver” with a plan, even when things seem to “suck righteously.” She feels Him with her as she first deals with the tumor. And In her most desperate moments, God is clearly all she has. Thrust into an MRI tube with a breathing tube down her throat, Jeannie fears she’s suffocating. She grasps for prayer in anguish. And by the time she makes it through the entire rosary, picturing each bead in her mind’s eye, she’s at a place of peace. “I never really understood meditation until I was near suffocation in an MRI coffin,” she writes. “I preferred to be in the MRI, alone with my peaceful meditation, than out of the MRI in the chaotic ICU.”

The easing of her pneumonia only leaves more time for Jeannie’s hunger — for food, water, speech and children — to gnaw at her. She grows intensely jealous of Jim every time he leaves the ICU, imagining him heading straight out for a giant cheeseburger. She seethes with resentment toward anyone who can eat. Returning to meditation, she again finds peace. “Without the rosary, I was a hideous monster,” she admits.

Even at her darkest, though, Jeannie avoids having a “God, how could you do this to me?” conversation. “Once I realized God was in this, that’s when things got better. Without Him, I would have been in hell.”

Amid this struggle, she is amazed that her parents and eight siblings drop their lives in Milwaukee, New York, Washington, D.C., and other places to rally in shifts at her bedside and provide Jim with support at home. Touchingly, individual brothers or sisters carve out unique and needed care specialties — lavender-scented foot rubs, podcasts or book readings to feed her mind, or gatekeeping when Jeannie needs a break.

That’s the family of the healing-power trinity evoked (along with faith and funny people) in the subtitle of When Life Gives You Pears. The other presence looming large at this nexus is Jim. No one — mortal, at least — is more integral to her recovery, body and soul.

When they’d married, they’d fit together perfectly, Jeannie had joked: “the oldest of nine children, the ultimate caregiver, and the youngest of six, the ultimate care-getter. A match made in codependent heaven.” Over the years, they’d largely remained these interlocking puzzle pieces, with Jeannie’s micromanagement handing Jim an avuncular “Sure, I guess I could take the kids to Katz’s Deli while they watch me eat a pastrami sandwich” role in the family. But her illness turns things upside down. They get through their share of strain, to be sure, particularly when she’s left unsuccessfully pantomiming her thoughts, before time, therapy, cortisone and surgery bring her voice back (and at long last, her mastery of swallowing too). But she is soon marveling appreciatively at Jim as he assumes her former role as “commanding general of the Gaffigan family.”

When Jeannie returns home — still with plenty of tubes and the bulk of her recovery ahead of her — Jim hits his stride, finding the comic mojo she’d missed dearly in the hospital. Grooming her, he prattles on in character as Mabel the stylist: “Honey, my third husband was cute as a button but dumb as a rock.” When she’s too weak to rise from bed, he pulls up as a courtly character known as “the horse.” “Your carriage is waiting m’lady,” he says, before lifting her and moving off to the bathroom with a clip-clop noise.

Jeannie sees the kids react to Jim in new ways — as if he’d know where the missing sock might be or wonder how a big school assignment had turned out. When he blurts out his frustration with feeling underappreciated — clearly Jeannie’s bailiwick — she senses completion of a Freaky Friday-style role reversal. A flood of empathy sets them on a new course, not effortless, that transforms their relationship. “We switched places. We had to experience what life must be like for the other person,” she says. “Because of that, we understand each other better, we trust each other more, and we love each other more.”

It’s one of many ways Jeannie’s journey of faith and recovery — like St. Ignatius’ before her — leads to a conversion. She realizes her insistence on being her family’s caregiver and “alpha controller” was feeding her ego as much as it was benefiting the children and Jim. She sees that loosening her grip will allow them to thrive. For this and other revelations, she’s grateful — and most grateful, improbably enough, for the spur that put her on this course in the first place.

“I’m grateful for my tumor,” she writes, “grateful that I could almost die to be more appreciative of life. Someday, I may just swallow water and not feel how good it is. I hope not.” If her old life was a hard pear that could be cut into perfectly angled pieces, a bit dry and lacking in flavor, her new life, Jeannie says, “is a misshapen overripe pear that mushes under the knife, but the juice is the sweetest thing you’ll ever taste.”

Wherever she is right now, you can be sure Jeannie Gaffigan is doing too much. That’s a given.

She’s more purposeful now, more deliberate with her energy, more alert to God’s call. She recognizes her creativity as a tool that can get people laughing — there will be always value in that — and a gift showing her connections waiting to be made that could nudge the world in a more gentle and just direction. Because she’s Jeannie Gaffigan, she’ll make those connections.

It’s been that way since those early New York days when she started putting the tenets of her Jesuit education to work, seeing teens on the streets and young actors with time on their hands and bringing them together to put on hip-hop Shakespeare. And it’s that way again.

When she finally got her life back from her brain tumor, she felt like Rip Van Winkle. Her oldest daughter was suddenly a teenager and her oldest son was right behind her. This was unfamiliar terrain. What to do with children who don’t always follow when she extends a hand? How to keep them on course without smothering them?

One answer came when she considered what happened to teens in the Catholic Church after their confirmation. The church seemed to lose track of them till their next big rite, marriage. So, Jeannie spearheaded the creation of a service-focused, post-confirmation youth group at her church. “Let’s do something so they can design and implement the things they want to do with their Catholic faith,” she explains. She and other mothers in their parish’s religious education program mentor the teens, the St. Patrick’s Warriors, in faith-in-action service projects. Since COVID-19 hit, the connections have been particularly rich. The Catholic teens have found allies: teens from synagogues, mosques and other Catholic churches. So, Jeannie helped found an interfaith group, the Imagine Society Inc., that has helped these teens mastermind valiant efforts to stock pantries with food and protective masks, deliver high-need items to pregnant mothers and newborns in homeless shelters, and to get hot restaurant meals to hospital workers, including some of the same nurses and doctors who so impressed Jeannie with their selflessness during her stay in the ICU.

At the start of the pandemic, Jeannie found herself praying — three different novenas across multiple days. Then, when distance learning arrived, those prayers became less formal but just as persistent. No longer a buddy — and more than a mystical figure and loving caregiver — God is her close companion now. “My prayers are now constant, always in my head and sound like ‘God, help me get through this insanely chaotic day,’” she shares. “But my prayers also sound quiet at night, like when I’m lying down with my 8-year-old, smelling his head as he falls asleep. I say, ‘God, thank you for my life and these beautiful children. I trust you will be with us no matter what the future will bring.’”