Every Halloween, when I see warnings to parents to check their kids’ candy in case someone has slipped edibles into the Sour Patch Kids, I have two thoughts in rapid succession: 1) Who would do that? Gummies are expensive! and 2) Remember Go Ask Alice? The supposed 1971 diary of a white teenage suburbanite who gets slipped LSD in a Coke at a party, then slides into addiction and ruin, contains multiple instances of “spiking”—the iconic first Coke; then, during a time when “Alice” is trying to get clean, the joints her former “grass gang” plants in her purse and locker; and, finally, the acid an ex-friend puts on her chocolate-covered peanuts, which drives “Alice” over the edge into psychosis.

The grim idea that innocent kids may become addicts without ever taking a drug on purpose, victims of a cruel and unforgiving youth culture, has been embedded in American life for decades, and Go Ask Alice was foundational to it. It was also all made up. Rick Emerson’s new book Unmask Alice is a dogged unearthing, and attempted undoing, of all the falsehoods that went into the production of Alice and the other teen journals “edited” by Beatrice Sparks, a housewife and devout Latter-day Saint from Provo, Utah.

When Alice hit it big, Sparks, an ambitious fiftysomething, had tried and failed to get published for years, living off her husband’s earnings in the oil industry while she churned out book proposals, advice columns, and pitches to agents. In one of the many interesting side stories packed into this book, Emerson explains that Go Ask Alice made it to market because of talk-show host Art Linkletter. Linkletter’s daughter Diane, barely 21, died by suicide in 1969, and Linkletter came to think this happened because she had been taking LSD. Sparks, hearing the story, pitched him on her idea of a diary of a lost girl, and it fit his priors. “It was the perfect pitch at the perfect time. It was, after all, a story Art Linkletter already believed,” Emerson writes. Linkletter’s literary agency got the manuscript—which came in the form of a stack of loose sheets and scribbled-over receipts shoved into a paper bag—to Prentice-Hall, where editor Kathryn Fitzgerald took it. Fitzgerald, overhearing a whistling colleague in the hallway, was the one who came up with the idea of pulling the lyric “go ask Alice” from the Jefferson Airplane song “White Rabbit,” and using it as the title. (The diarist goes unnamed throughout the book, adding to the mystery.)

Because Sparks had sold the manuscript as a “real diary,” which Fitzgerald then did the work of putting together, she couldn’t get her name onto the book. The publishing company, quite rightly, thought that teenagers might be less likely to read something with an adult’s name on the cover, and since Sparks didn’t claim to have written the diary, she couldn’t complain. Emerson surmises that this must have driven Sparks wild with frustration. As Emerson finds when surveying reviews, newspapers across the country took Alice as fact—with some exceptions. Even so, screenwriter Ellen Violett, who adapted Alice for TV in 1972, remembered hearing all around Hollywood that Alice was fake.

After Alice, Sparks pitched a series of follow-ups, which she hoped would have her name on them, including self-help books and her story of fostering a Navajo teen. They went nowhere. “Everything read like a first draft, with lots of flailing and repetition,” Emerson writes. “Worst of all was Sparks’ tone, which clucked and scolded like an angry bluebird, equal parts cheer and fury.”

What worked was going back to the “found diary” trick. The middle section of Emerson’s book is about Jay’s Journal, a less popular but still respectable-selling follow-up to Alice, which was based on the life of Alden Barrett, the teenage son of another LDS family living in Utah. Alden died just as Alice was taking off. A sensitive and bright teenager who suffered from depression, he had been at constant odds with his family—questioning the doctrines of the LDS church, stealing pills, briefly running away. After a bad breakup with a girl who loved him but whose parents blocked their relationship, he died by suicide in his parents’ home. He left behind a diary.

Alden’s mother, Marcella Barrett, gave that diary to Beatrice Sparks, against her husband’s wishes, thinking that she could publicize Alden’s life so that other people could see warning signs in their own children. Sparks made it into something totally different: a story of “Jay,” who, over the span of 18 months, drinks and takes pills, then starts using a Ouija board, then moves on to serious Satanism. He has a midnight cemetery wedding ceremony with his girlfriend, where they slash their tongues before kissing, so that their blood mingles together, and then kill a kitten. He’s later possessed by a demon named Raul. Sparks used two dozen entries from Alden’s diary and then added 190, “including all of the violent and occult material,” Emerson notes. The result of this audacious fabrication was, for Alden’s family, catastrophic. They were ostracized in their town, and Alden’s gravestone was desecrated and stolen; the parents divorced, and the rest of the family scattered, leaving their community behind.

There is a gothic quality to all of Sparks’ stories of teen ruin. If Sparks, who died in 2000, were alive today, she would find a welcome home in the QAnon-adjacent online community, producing some of its best underground-tunnel fan fiction. Some of Alice is incredibly lurid: When “Alice” is having her psychological breakdown, she sees her grandpa’s worm-infested corpse trying to embrace her, and then she feels flies and worms all over her body—eating parts of her that include, as the book is careful to detail, her vagina. “Alice was brutal, shoving your face in shit,” Emerson writes. In the early ’90s, Avon Books published Sparks’ It Happened to Nancy, a book about a girl who falls in love, has sex with an older man, and dies of AIDS, moving from diagnosis to death in a lightning-quick 23 months. In Sparks’ world, teenagers—especially girls—are so fragile, they can basically implode upon contact with the world.

Most reviews of Unmask Alice focus on Go Ask Alice, which is fair; it’s the most iconic of Sparks’ oeuvre. But Sparks was eventually to publish a shelf full of books of this kind, and I find their massed ranks equally fascinating. Besides Voices, Nancy, and Jay’s Journal, there’s Treacherous Love (about a teen seduced by a teacher); Annie’s Baby (a teen mom); Almost Lost: The True Story of an Anonymous Teenager’s Life on the Streets (a runaway); and more. By the end of her career, Sparks had figured out that she should say, when asked about where she got these tales, that these were stories from her “patients.” But “there were no case studies. There were no patients. There was no clinical practice,” Emerson writes indignantly. “Beatrice Sparks was no more a psychologist than she was a Sasquatch, and even a lazy editor could have unraveled the lies with a single phone call.”

In the New Yorker, Casey Cep takes issue with Emerson’s single-mindedness in pursuit of Sparks’ wrongdoing, writing: “Emerson’s belief that anything bunk should be debunked is undermined by the Torquemada-like zeal with which he tries to hold one huckstering grandmother responsible for international moral panics and the dishonest tactics of the publishing industry.” Does he get overzealous? In places. In some sections, which get long and baggy with detail, he clearly could have used a strong editor. But Sparks’ responsibility for today’s new culture of moral panic around the lives of teenagers and kids isn’t small. The flare-ups of the Satanic Panic era did real damage—say, to Alden Barrett’s family, or to the people accused of molesting kids in tunnels under day cares—and although many now debunk and reject stories from that era, others still seem to harbor a suspicion that some of that might have been real. Publishing houses who have reaped the profits of Sparks’ work know that it’s not just moral-panicky Mormons and present-day Moms of Liberty who could find themselves awake at 3 a.m., wondering what will happen when their kids meet the world.

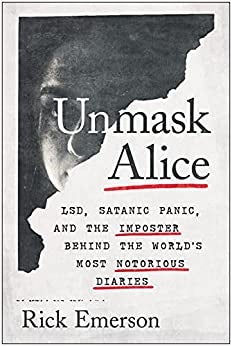

Unmask Alice: LSD, Satanic Panic, and the Imposter Behind the World’s Most Notorious Diaries

By Rick Emerson. BenBella Books.

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page. Thank you for your support.

That’s why Unmask Alice is more than the story of a (frankly) somewhat deranged older lady who let her imagination and ambition and self-righteousness run away with her. I was struck, reading it, by the fact that the talk-show host Art Linkletter was (besides Diane’s father) the originator of Kids Say the Dardnest Things!, an interview segment on his show that became a compilation that sold more than 5 million copies in 1957. Kids between the ages of about 3 and 8, as anyone who’s had one (or been around one) knows, blurt forth random sentences that are like glimpses into another world. (My 5-year-old, after losing her first tooth recently, told me that the tooth fell out on her mattress overnight, “then just LAY there, telling me secrets.”) Parents treasure those moments, because they suggest so much more lies behind the curtain; they also come from children who are young enough to still be willing to share.

Then the kids keep growing, and maybe don’t say as much, parents must learn to manage their anxiety about all the unknowns—or, they go down a bad road, clamping down hard and letting their worst fears rule the roost. Books like Sparks’ speak to the darkest fears of parents whose kids’ minds and lives have become obscure to them. And they still appeal to somebody. On Amazon, Alice has four-and-a-half stars.