As I read Imani Perry’s sophisticated Looking for Lorraine, which digs up the oft-overlooked life and work of activist and writer Lorraine Hansberry, I remembered New York Times film critic A.O. Scott’s review of I Am Not Your Negro, Raoul Peck’s 2017 award-winning film based on an unfinished manuscript by James Baldwin. In his review, Scott argues that the film is “more of a posthumous collaboration, an uncanny and thrilling communion between the filmmaker … and his subject.” Looking for Lorraine, which Perry suggests is “less a biography than a genre yet to be named—maybe third person memoir,” conjures a similar spirit of communion. Using her own personal interest in Hansberry—best known today as the playwright of A Raisin in the Sun—as narrative scaffolding, Perry mines Hansberry’s life, her indefatigable radicalism, and her queerness, and she prods us to consider what this fuller portrait of a categorically transgressive figure reveals about the state of social justice today.

The title of Perry’s book nods to Looking for Langston, an impressionistic 1989 film by Isaac Julien that, while dedicated to Langston Hughes, centers more broadly on queer black life during the Harlem Renaissance. In Perry’s words, “As [Julien] looked for Langston in footage, language, and imagination, I look for Lorraine in words, ideas, and imagination.” And she begins her search with Hansberry’s birthplace: Chicago.

While Hansberry’s family lived comfortably—her father, Carl, was a successful real-estate broker—she quickly learned, as a child, that her relative prominence was no armor against a racist world. After her father began challenging racially restrictive housing covenants in Chicago in the 1930s, the family lived under relentless threat of attack by white mobs; Hansberry’s mother, Nannie, spent evenings guarding the family’s house with a German Luger pistol. That Jim Crow threatened all black Americans, class or any other scraping of privilege be damned, profoundly shaped Hansberry’s broad black consciousness. Years later, at a rally in 1963, she declared that “between the Negro intelligentsia, the Negro middle class, and the Negro this-and-that—we are one people. … As far as we are concerned, we are represented by the Negroes in the streets of Birmingham!” Perry also explores how both she and Hansberry were influenced by their fathers: Perry’s was a Jewish communist with a tenacious belief in black liberation, and Hansberry’s was a civil-rights activist who fought discrimination until, as his famous daughter told it, “American racism helped kill him.”

Yet Hansberry’s passion for social justice stretched beyond America’s borders. Perry spends a meaningful portion of the book charting Hansberry’s experiences abroad. For instance, while she was briefly an undergraduate at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, she spent the summer of 1949 in Ajijic, Mexico. Despite its tiny size, the Mexican city had long attracted artists from around the world. For the preternaturally talented Hansberry, Ajijic wasn’t merely some college sojourn: “it is clear that Ajijic was a place where her sense of possibility for her own life, her sense of romance and joy, was expanded and excited,” Perry explains. She rightly refrains from speculating too much about young Hansberry’s intimate life, but it’s hardly a leap to see how her time there—learning from indigenous and queer artists in what was, essentially, a bohemian oasis—must have nurtured her eventual embrace of her own artistic and sexual autonomy.

In addition to Ajijic, Hansberry traveled to Montevideo, Uruguay. She went there in 1952 for the Inter-American Peace Conference in place of Paul Robeson, who had recently been stripped of his U.S. passport. It’s in these pages that we can see the vastness of Hansberry’s gaze as an activist. Of a march against police violence she joined while in Montevideo, she remarked that “there were police along the streets with their long swords at their sides and their arms crossed and their faces drawn into those long sober expressions peculiar to police all over the world.” Indeed, what made Hansberry a radical was partly her recognition, despite geography, of the enormity of injustice. As Perry recalls, “When I was a child, radical was a compliment my parents gave to people whom they considered smart and politically righteous.” (It’s no surprise, then, that Perry’s father, too, was a Hansberry acolyte: that he revered her “for her radicalism, for her unflinching truth telling, and for being a seeker.”)

Perry dedicates most of her attention to Hansberry’s life in New York, the place she called home beginning in 1950. For a short time, she attended the New School for Social Research, until she dropped out and started working at Robeson’s pan-Africanist newspaper Freedom, which she believed “in its time in history, ought to be the Negro journal of liberation.” Hansberry also met the songwriter and publisher Robert Nemiroff, whom she married in 1953. His later success—he co-wrote the 1956 chart-topper “Cindy, Oh Cindy”—gave Hansberry the financial stability she needed to write full-time. In 1959, her most famous work, A Raisin in the Sun, about a poor black family living in Chicago (living, in fact, in an apartment not unlike the one Perry lived in for part of her youth), debuted on Broadway and turned her into a celebrity; Baldwin later reflected that “never before, in the entire history of the American theater, had so much of the truth of black people’s lives been seen on the stage.”

One of the challenges of writing about Hansberry is discussing her sexuality—and that’s because she wasn’t out, at least publicly, while she was alive. She certainly advocated for gender and sexual equality, and Baldwin, who was open about his own sexuality, was a close friend. In the late ’50s, Hansberry also began exploring the growing homophile movement and dating women, even while she was in a straight marriage—something Nemiroff supported.

And yet, most of what we know about Hansberry’s identity as a lesbian stems from her private writings: essays, letters, poetry, short stories. Perry treats these texts (many of them available only since 2010) with care, tenderly pulling back the veil on a woman who committed her craft to investigating the various facets of identity. In 1960, for instance, Hansberry wrote two lists: “I like” and “I hate.” On the former, she wrote things like “Eartha Kitt’s looks,” “Older Women,” and “My homosexuality.” She included “My homosexuality” on the latter, too. These two lists, Perry writes, illuminate the splendor and pain Hansberry—“the passionate and opinionated intellect and the aesthete”—felt when it came to her sexuality, to the emotional wrestling she kept mostly hidden away: “It is a testament to the delicate strength of her pen that even this exercise in simple accounting became poetry.”

Perry’s concluding pages retrace “the places Lorraine stood.” In a diaristic manner, she recounts her travels in 2017 to Greenwich Village and Harlem (among other places), searching for signs of Hansberry. (There’s less of her in the former, she explains, noting that in lieu of the midcentury bohemia are “cool accumulation and edgy wealth.”) This literal looking for Lorraine transposes Hansberry into the present, into the Black Lives Matter era—and Perry isn’t timid about pointing out how contemporary society still buckles morally on some matters of acceptance. “Where would her place be?” Perry asks. “In Boystown—an expensive upper-crust queer community where her brownness would still be an oddity? Probably not. Although her love of women would be treated more kindly today, there is a good chance Lorraine’s sexuality would be used to push her away from the center of American theater and thought.” Even today, Perry reminds us, one form of oppression all too often crosshatches with, and props up, a litany of others.

In fitting herself into Hansberry’s story with autobiographical elements, Perry offers a bracing air of familiarity and urgency around the artist, whose legacy has faded since her death from cancer in 1965. (She was only 34 years old.) By crisscrossing then and now, Perry insists how important it is that our connection to this history—to Hansberry—survive. Because by learning more about her—revisiting the keen ways in which she interrogated America and its endless betrayals—we, too, are encouraged to become our best and most radical selves. “Lorraine rejected the American project but not America,” Perry writes. “She saw her embrace of radical politics as a commitment to it, to what it could be.”

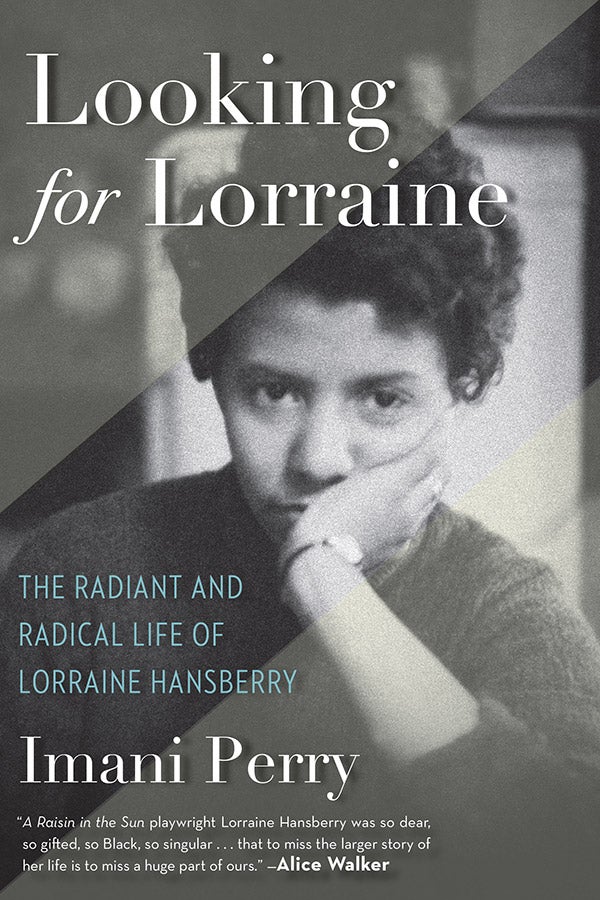

Looking for Lorraine: The Radiant and Radical Life of Lorraine Hansberry by Imani Perry. Beacon Press.

See all the pieces in the Slate Book Review.

Slate is an Amazon affiliate and may receive a commission from purchases you make through our links.