Well, that certainly was easy. All it took was a single threatening letter from S.C. Attorney General Alan Wilson, and the Charleston County School Board folded — quietly conducted a do-over Monday of votes that Superintendent Don Kennedy acknowledged were taken in violation of the state’s open meetings law.

From start to finish, the whole matter took less than two months to resolve. Without requiring individuals to spend their own money to force the district to comply with the law, without wasting judicial time on hearings and a trial and years of appeals, without the attorney general’s office or the school district having to hire outside attorneys — or use more than de minimis time of their internal counsel.

Compare that to what’s happening in Richland School District 1, where a resident filed suit in August 2021 alleging that the school board had held numerous closed-door executive sessions on topics ranging from using schools for polling places to a board member's plans to resign, all in violation of state law. More than a year and 50 court filings later, the parties are still arguing over what questions can be asked in depositions.

Or what’s happening in Lexington-Richland District 5, where Columbia’s State newspaper also filed suit in August 2021, alleging that district illegally voted in a closed-door session to approve a payout for a departing superintendent. The docket is similarly lengthy, and a resolution is similarly nowhere in sight.

The issue in Charleston County wasn’t voting or discussing matters in secret sessions that the S.C. Freedom of Information Act requires be discussed in public. It was about a much more mundane requirement of the FOI law: that public bodies inform the public at least 24 hours in advance of what they will discuss at their meeting. That’s a crucial provision that’s designed to ensure that we can show up and have our say when officials consider actions that interest us; when it’s violated, it’s as if the body had met in secret.

The courts routinely side with plaintiffs who sue school boards and state and local governing boards for violating the Freedom of Information Act. But this hasn’t served as a deterrent for the steady flow of violations, likely because the boards know that in most cases, individuals aren’t going to invest the time and money needed to take them to court — or stick with those lawsuits when they have to go up against government attorneys who are expert at drawing out the cases as long as possible.

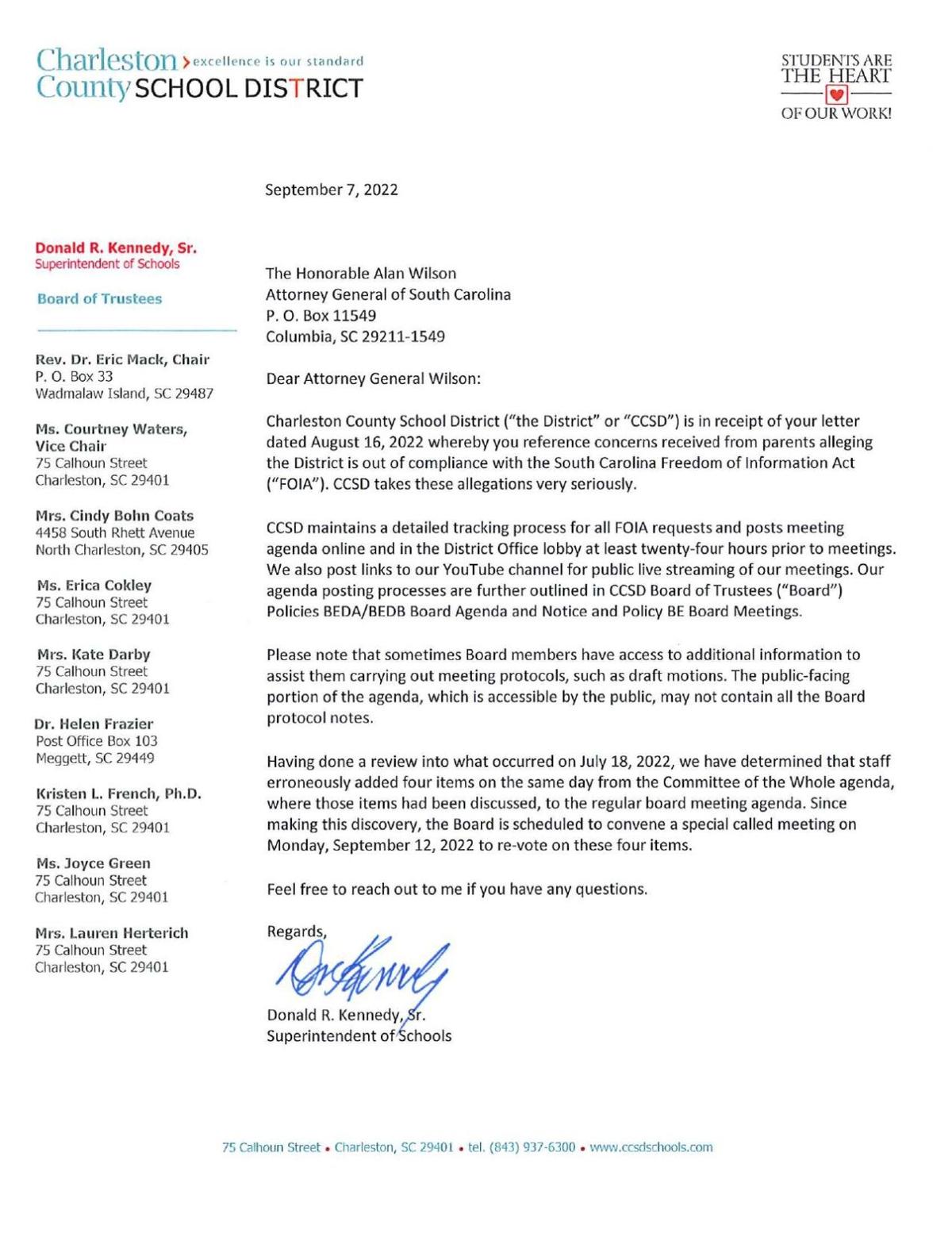

We can debate whether we believe the Charleston County School Board’s illegal votes at its July 18 meeting really were the result of a staff error, as Mr. Kennedy wrote in his Sept. 7 response to Mr. Wilson, or a deliberate decision by the board to ignore the law after Board Member Cindy Bohn Coats argued that the public wasn’t given proper notice of what would be discussed. But the district’s hasty acknowledgement of its mistake and quick correction demonstrate how important it is for the attorney general to get involved in such matters.

Would the district have backed down so quickly if Mr. Wilson had called it on a more significant violation — like, say, its illegal closed-door discussion last year about COVID policy? We can’t say for sure.

But we feel pretty sure about this: If Mr. Wilson would do this sort of thing more often — even for smaller violations that don’t really affect policy — the district would get the message pretty quickly. As would other districts and councils. And state agencies.

And if they don’t, he could bring criminal charges of misconduct in office against board members with a pattern of violations, as he threatened in his letter to the Charleston school board. And he should.